If you bottled up a caricature of Southern culture and poured it all over a town, you would get Gatlinburg, Tennessee. The streets of Gatlinburg look more like the midway of a low budget, small time carnival than an actual town. Everything from mountain cabins to southern cooking and moonshine to grits are commercialized and distilled to absurdity. If the South has an armpit, it is this town in the corner of Tennessee. Minutes from my hotel, itself homage to the worse of this town, paradoxically lies one of the most beautiful places in the South— Great Smoky Mountains National Park. My wife and I are here in early June to witness one of the most spectacular displays of biology found in the South, the lightning bug Photinus carolinus. About 30 minutes after sunset, thousands of males light up the forest in the former logging town of Elmont, now in middle of the park. The males are known to flash in synchrony, signaling and then going dark in unison.

Two months before, everyone around me witnessing the light show, was sitting in front of his or her computers to gain a ticket. Thousands of these tickets went in just 24 hours in April to see the insect light show in June. Scientists use a model developed by Lynn Faust and Paul Weston in 2009 to predict when the actual light show will occur. The model uses growing degree-days, a tool also used to predict when flowers will bloom. Think of the model as a bag. One fills this bag with temperature coins gained when the average daily temperature exceeds some base temperature. When the bag is full of temperature coins the lightening bugs emerge and being lighting up the forest floor. For Photinus carolinus, the base temperature is 50˚F. If the day temperature is 80˚ and the night temperature is 40˚, the average is 60˚. This is 10˚ greater than the base so you get 10 temperature coins to add to the bag. Males typically emerge from larvae at about 840 coins with the peak display at 1,069 coins, which also coincides with when females emerge. Scientists start counting coins at the start of March. By April, park scientists know the week and half the light show will occur.

Two months before, everyone around me witnessing the light show, was sitting in front of his or her computers to gain a ticket. Thousands of these tickets went in just 24 hours in April to see the insect light show in June. Scientists use a model developed by Lynn Faust and Paul Weston in 2009 to predict when the actual light show will occur. The model uses growing degree-days, a tool also used to predict when flowers will bloom. Think of the model as a bag. One fills this bag with temperature coins gained when the average daily temperature exceeds some base temperature. When the bag is full of temperature coins the lightening bugs emerge and being lighting up the forest floor. For Photinus carolinus, the base temperature is 50˚F. If the day temperature is 80˚ and the night temperature is 40˚, the average is 60˚. This is 10˚ greater than the base so you get 10 temperature coins to add to the bag. Males typically emerge from larvae at about 840 coins with the peak display at 1,069 coins, which also coincides with when females emerge. Scientists start counting coins at the start of March. By April, park scientists know the week and half the light show will occur.

My wife and I jockeyed for our position at 7:00 pm, among hundreds of tourists, to observe this magnificent display. At approximately 8:30 the sun begins to set and by 9:00 the flashes begin. My wife and I are done and head out nearly an hour before the males stop flashing. Male will keep the display going for up to three hours. Photinus carolinus males are extremely motivated to keep the flashing going. They are evolutionary pawns in the age-old tale of attracting a female. The males signal in flight, while females lay low in the leaf litter. Indeed, females are rarely seen flying. During the dark phases, approximately three seconds after the last male flash, receptive females will signal with a double flash.

My wife and I jockeyed for our position at 7:00 pm, among hundreds of tourists, to observe this magnificent display. At approximately 8:30 the sun begins to set and by 9:00 the flashes begin. My wife and I are done and head out nearly an hour before the males stop flashing. Male will keep the display going for up to three hours. Photinus carolinus males are extremely motivated to keep the flashing going. They are evolutionary pawns in the age-old tale of attracting a female. The males signal in flight, while females lay low in the leaf litter. Indeed, females are rarely seen flying. During the dark phases, approximately three seconds after the last male flash, receptive females will signal with a double flash.

Amongst the forest floor light show, select males and females begin their close range mating dialogue of light. The males will switch from multiple flashes to a single aimed flash as he circles the female. As he approaches the female flashing his lantern, he first flies then walks. Within minutes, the couple will move to a discrete and sheltered location to seal the deal.

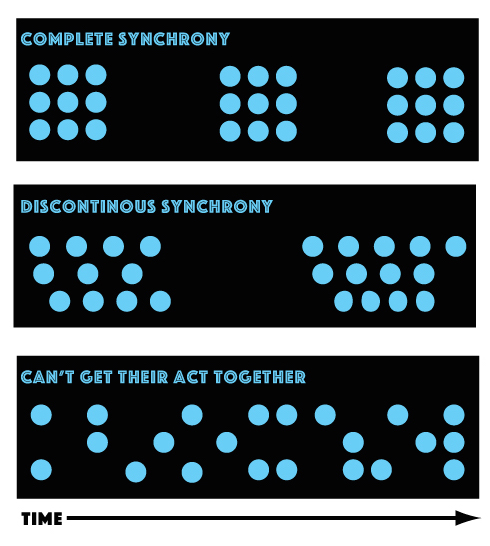

The combined flashes of males light up the forest floor in every direction around me, a disco light party fueled by biological blue-white LEDS illuminates the forest floor. Each male produces a train of 4-11 flashes, on average between 6-7, in half-second intervals followed by 6-9 seconds of dark. The flashing is a discontinuous synchrony. For ten seconds or so, males will flash multiple times in the period, each at their own pace. After about ten seconds, the forest goes completely dark. Eight seconds later the forest floor is lit up once again.

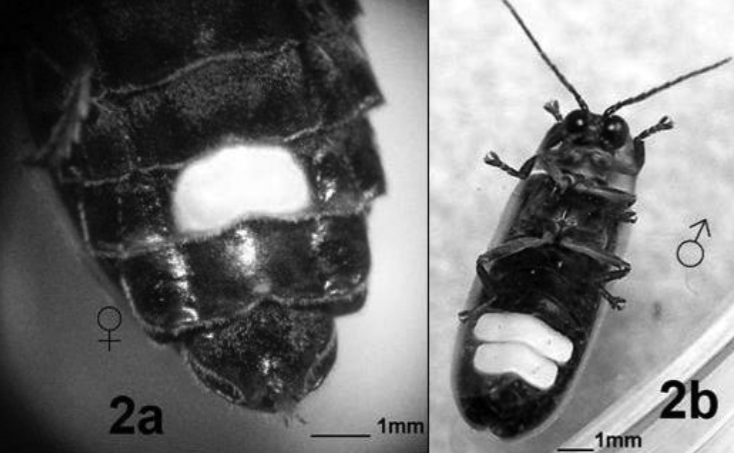

The reason for the male synchrony is unknown. Jonathon Copeland and Moiseff Andrew in 1994 speculated the rhythmic light show is due to weak female flash. The female possess a single half-moon shaped lantern while males possess two lanterns. A bunch of males, with 2x the lightening power, would swamp out the female’s signal. Or because this occurs in the dense vegetation of the Smoky Mountains, synchrony could extend the intensity of any single male’s flash. I think it all happens because a single male starts off, saying with light, “Pick Me!” This causes a cascade of males all to respond, “No Pick Me!” This happens repetitively for a few seconds until all the males get tired. They rest up and the show starts again.

The reason for the male synchrony is unknown. Jonathon Copeland and Moiseff Andrew in 1994 speculated the rhythmic light show is due to weak female flash. The female possess a single half-moon shaped lantern while males possess two lanterns. A bunch of males, with 2x the lightening power, would swamp out the female’s signal. Or because this occurs in the dense vegetation of the Smoky Mountains, synchrony could extend the intensity of any single male’s flash. I think it all happens because a single male starts off, saying with light, “Pick Me!” This causes a cascade of males all to respond, “No Pick Me!” This happens repetitively for a few seconds until all the males get tired. They rest up and the show starts again.